The sociopolitical landscapes of Indigenous Latin America are understood most clearly when Indigenous identities and histories themselves are understood as dynamic and ever-changing, but textual explanations often lack the abstract ability to communicate the validity of these fluid identities and the juxtaposing relationship between historical fact and lived experience. When the dynamism of identity or history is flattened in texts, the idea of fluidity can be easily misinterpreted as a distortion of facts or historical truths based in dominant perspectives.

But adapting such a complex idea of Indigenous Latin American identity and history into artistic mediums that are themselves dynamic and fluid, the abstract language of visual arts surpasses text's communicative abilities. The conceptual visual works below convey the naturally dynamic nature of identity and history as a means of re-situating Inidgeneity in a present and as essential for processing historical trauma, therefore providing the viewer with visual evidence of how the dynamic nature of identity and history is natural rather than distorted.

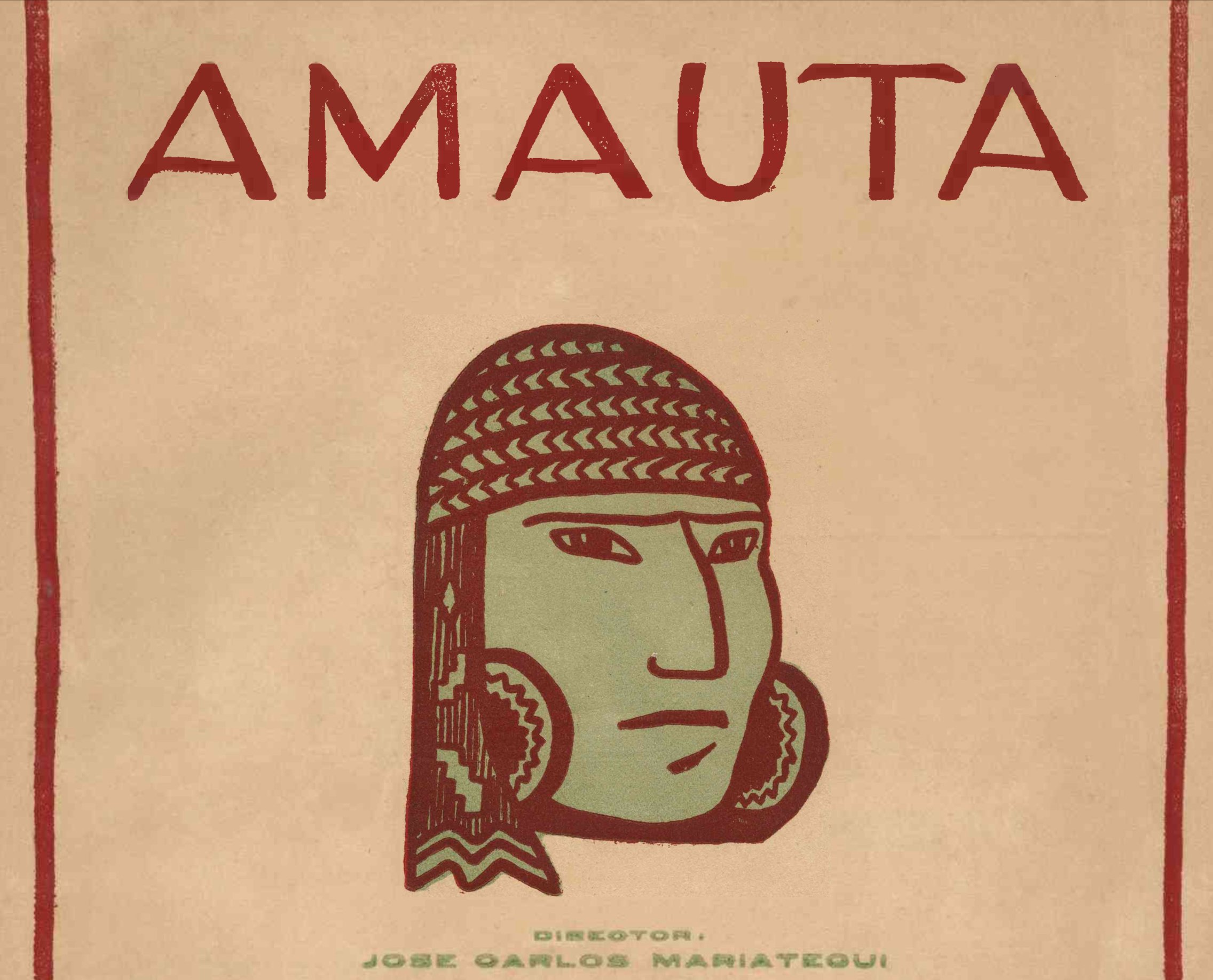

JOSÉ SABOGAL'S WOODBLOCK COVERS OF AMAUTA

All printed from the same woodblock carving of an Indigenous figure dawning a traditional, Andean style chullo, the figure's shape and outlines remain the same in each print, but the change of the design's colors visually reflects the dynamism of Indigenous identity that is ever-changing with and intrinsically tied to current social contexts.

Red overlaid with black - the design reflects a state of Indigenous identity that is situated in political urgency or is more culturally visible in the current social climate. In olive-greens and neutral tones - the design reflects a change in the role land has in shaping Indigenous identity, with land rights issues having more current prominence. Embedded within the body of the publications text and printed in simple black outlines - the design conveys Indigenous identity as being both something that is changed by and changing the current issues discussed in the surrounding text.

Never arrested in a pre-Colombian past, Indigenous identity in these woodblock prints changes colors cover-to-cover, in the visual and conceptual portrayal of Indigenous identity as dynamic, ever-changing, and absolutely a part of modern Peru. The viewer is left with a beautifully clear representation of the dynamic nature of Indigenous identity as constantly changing with modern issues.

FRANCOIS BUCHER'S 'UNITED'

The unconventional banana canvas of this piece is not only emblematic of the exploitation of Indigenous communities throughout Latin American farming industries, but the unconventional canvas also uses the natural browning of the banana's skin to visually communicate the natural, dynamic, and ever-change nature of "historical truths" over time. The gradual visual development of the word "UNITED" scored into the fruit's skin, delivers a powerful message and visual example of how broken treaties and historical violences against Indigenous Latin American communities can initially be seemingly insignificant, but later re-read as much more violent and clearly malicious over time. These historical violences deepen and become darker, slowly embedding into not only the past, but also the present and futures of Indigenous communities. When told from dominant narratives, often it's the "initial scratch" that serves as the foundation of textual recollections of these "historical truths," while the dynamic, changing, and darkening lived experience of Indigenous people are rarely used to amend those historical narratives.

This piece visually begs viewers to reconsider Indigenous histories themselves as dynamic and ever-changing, providing visual evidence of how a historical trauma that may have initially been faint, slowly leaves deep wounds in a contemporary Indigenous Latin American landscape. Like Indigenous identity, the visual communication of history as fluid, allows viewers of this piece to reconsider the textual historical narratives that they have considered as truths, and ask themselves if what they had read prior was nothing more than that textually flattened, faint scratch.

JIL LOVE’S ‘PROCESÍON DE LAS 43 LLORONAS’

This subversive performance piece clearly demonstrates how something “set in stone,” can change, regardless of previous notions of objective understanding or unchanging narratives. Throughout Mexico, northern Central America, and southwest United States, there is a general familiarity of La Llorona, but her narrative is still subjective country-to-country, state-to-state, person-to-person. Serving as an important medium of simultaneously subjective and collective knowledge, ‘Procesión de las 43 Lloronas’ proves effective in providing the visual and conceptual space for historical traumas and ideas of another’s identity to be dynamic, subversive, and changing in conjunction with one another. A public procession through Mexico City’s Plaza de la Constitución, the 43 La Lloranas figures challenge the state’s “historic truths” surrounding the 43 students who went missing in 2014.

Previous notions of La Llorona’s identity as a loudly weeping figure, who roams alone at night, and who is responsible for murderer of her own children, are now challenged by the silence they bring through the plaza, as a group of figures in broad daylight are now the ones who mourn the students that had been disappeared not by her, but by the state. Taking these prior understandings of the identity of the figure and the historical truths surrounding the missing forty-three students, this visual performance piece subverts those previous notions and provides viewers with the visual evidence needed to convey how little these identities and histories are actually set-in-stone, and how a dynamic shift in Indigenous identity can be influenced by and be in conjunction with the narrative changes in Indigenous Latin American histories.